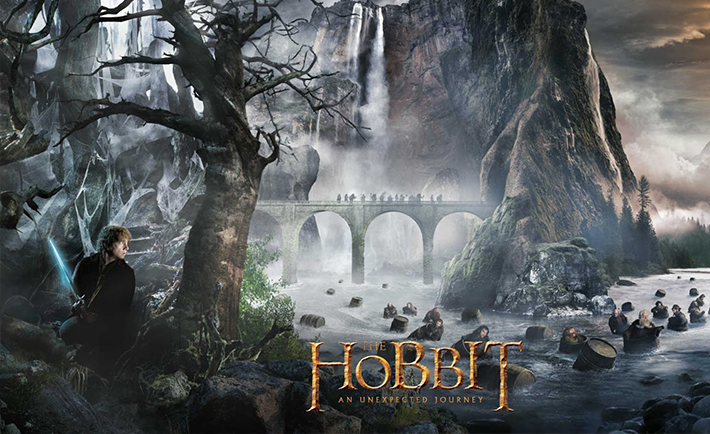

This Christmas will see the release of the second Hobbit film, Peter Jackson’s fifth adaptation of a JRR Tolkien book. Set to be one of the biggest releases of 2013, it is a sign of the times, as the number of films adapted from books, comics or even older films increases by the year. As this continues, the debate is repeated – is it right to change the book when making it into a film? These are three films which argue that it is.

The Lord of The Rings Trilogy

JRR Tolkien’s fantasy follow-up to The Hobbit nowadays seems perfect for the big screen. It has likeable heroes, sinister villains, epic battles and even one or two love triangles. It is, on paper, a blockbuster movie. It is strange to note, however, that for a very long time it was considered unfilmable. Yes, it had its action and romance, but there was also a lot of conjugating verbs in Elvish, not to mention the appearance of Tom Bombadil, a character that even Tolkien admitted he didn’t understand. In order for it to be adapted for cinema, changes had to be made. Peter Jackson found the balance between a piece of literature and a blockbuster film, and made the necessary alterations to the plotline in order to do so. The films were released to critical acclaim and were generously awarded, a definite argument in favour of the changes.

Fight Club

Fight Club, as a book, was in many ways a cult movie waiting to happen. Chuck Palahniuk’s novel about rebellion against modern society was unique, deeply insightful, and most importantly, darkly hilarious. Adapted directly from the book, it probably would have gained modest success, but it was when David Fincher got his hands on the story that it managed to realise its full potential. Fincher, fresh from Se7en, took the script and tightened up the screws on a somewhat erratic story. Taking the book’s intended message and running with it, Fincher altered certain details, numbering the famous rules and completely overhauling the ending, finishing up with a movie that Palahniuk himself believed to be an improvement on his book. Now resting comfortably in the top 10 of IMDB’s top 250, David Fincher’s changes managed to ensure that the first two rules of Fight Club will continue to be broken by legions of loyal fans.

Where the Wild Things Are

Where the Wild Things Are is a children’s book that was released in 1963 which boasts vibrant pictures on each page and very little actual writing. It is the story of a young boy who loses his temper and is scolded, only to run away to a far off land full of monsters, where he fits in. At first glance, it is a typical children’s book. It’s surprising then to learn that, upon it’s release in 1963, it was banned in libraries and heavily criticised. It took two years of children flocking to the book before critics began to lighten up about it, and then the acclaim started to flow. The book went on to be lauded for its use of emotion with the child’s turn to his wilder side as a result of his tantrum.

What was considered revolutionary in 1963, however, has become much more mundane today, and it was with that thought in mind that director Spike Jonze set about updating the story for film. The film’s plot is similar to the book’s at the most basic level, and follows the same template, but amps up the raw emotion, using its surreal setting and characters to personify the deepest of emotional fluctuations, and the difficulty a child might have in understanding them. It takes the sentiments delivered by the original book and delivers them to a modern audience in a way that it understands. Sendak himself collaborated on the film, and it shows, as its changes make it a perfect modern representation of the themes of the original book.

Shane O’Neill

Leave a Reply