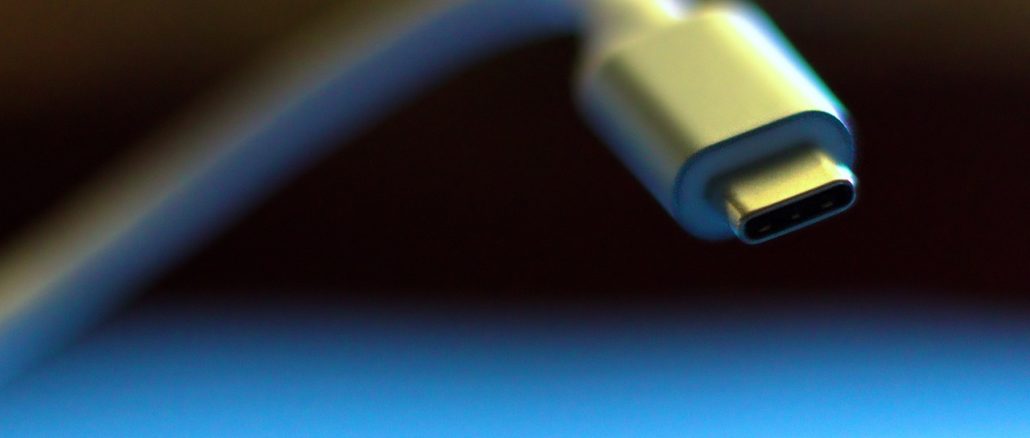

The European Union have announced a new regulation for all mobile devices to adopt the same charging cable by 2024.

This new EU law will make it mandatory for all technology companies to provide a USB-C charging port for their products with 2024 declared as the deadline.

The European Union has stated that “the legislation covers mobile phones, tablets, digital cameras, headphones, headsets, handheld videogame consoles, portable speakers, e-readers, keyboards, mice, earbuds and portable navigation devices”.

This would prescribe charging cables for separate electronic devices to be interchangeable, with Apple being required to transition to a USB-C charging cable and discontinuing their infamous lightning port within the European market.

Apple had originally protested this EU proposition, but recently Greg Joswiak, a senior executive in the company said at a tech conference that “obviously we’ll have to comply, we have no choice.”

This law offers consumers obvious conveniences in having a universal charging cable instead of variants for a series of devices. While also advocating important environmental considerations regarding electronic waste and the importance of sustainability.

However, the explicit issue is the technological limitations this impending EU law will subsequently moderate.

Instead of technology companies freely testing out better charging models or cables efficiently, corporate manufacturing will have bureaucratic uniformity that restrains innovation.

Even if a greater charging cable or device requirement is developed, such innovative companies will need EU permission to make hypothetical changes in the future. But unlike big tech, government bureaucracy is a slow, mechanical and sterile process often resistant to change.

The core issue with this law is not the change from one connector type to another, in fact many Android devices already use the incoming standard charging cable (USB-C).

A charging connector is merely a tool to power portable electronic devices, while wireless charging models do currently exist maybe this is where innovation practises is key for an environmental and truly modern balance in the future.

But the principled issue found in this debate is the heightened example of governing regulatory virtue, that conceivably dispenses with such enterprising innovations and the intrinsic evolution of mobile technology, that is not attributed to government.

But if government want a direct say in product design and commercial aesthetics, what else could become civically standardised in the future?

Jack Redmond