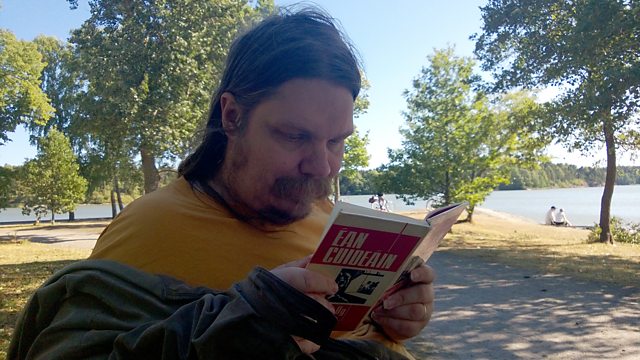

[dropcap]The[/dropcap] sun setting over the Lake District of Varkaus, an industrial town in Eastern Finland, Panu Höglund ponders the state of the Irish language, how he could improve other’s experiences of learning it. Beside him is a copy of a book he had purchased, written in Russian, tempting him from sitting down to an evening’s internet browsing and corresponding with other Irish fanatics. He waits for my message, greeting him and commencing the interview we had organised the week before.

Having read a selection of his material in secondary school, I was familiar with the works of the Finnish enigma that is Panu Höglund, an Irish-language writer whom very rarely visits the Emerald Isle despite his commitment to the land’s native tongue, his imperious command over it compelling me to interview him and to unearth his story. Throughout the years, hearing that ‘An Ghaeilge’ was a ‘dead language’ and that soon it would be extinct, I felt obliged to investigate the doubts people had on its behalf, and to see its importance in the lives of non-Irish nationals. Höglund, being an esteemed author, seemed to be the perfect candidate for this interview.

With that, a chat box popped up on Panu’s screen, focusing his wandering mind and allowing him to tell his life’s story.

In the Southern Finnish municipality of Hämeenlinna, Höglund was born into a life in which he would go on to commit to enhancing his own and others’ understanding of languages, Irish being a particular favourite of his despite there not being a drop of Celtic blood in his Scandinavian frame. In his fiftieth year, Höglund boasts about having become highly proficient at reading, writing and speaking Swedish, Russian, Polish and English, as well as being a native speaker of the Finnish language. However, he has only published his work ‘as Gaeilge’, it being the most obscure language in his impressive lingual repertoire.

Returning to his days as a child, Panu recalls living in the relatively small area of Kalvola in which he occupied his knowledge-thirsty self by watching documentaries and reading books he had purchased second hand. It was, in fact, one of the many documentaries he used to watch through which the author and linguist became captivated by the Irish language and the culture surrounding it. After coming across a copy of “Learning Irish” by Micheál Ó Siadhail whilst in his late teens, Höglund set about mastering the tongue, so alien to him, and through friends he had made from Ireland he received copies of Irish-language classic novels, such as ‘Peig’ by Peig Sayers and ‘Rotha Mór an tSaoil’, a biography telling the life story of a travelling Irishman named Micí Mac Gabhann. Through nothing other than his own perseverance and a keen interest in foreign cultures, Panu Höglund went from being a man living 3,000km from Ireland to being one of its most reputable Irish-language authors.

Looking to delve further into the connection the ‘Fionlannach’ had with the language, I asked how important it was in his life and how much of an impact it had had on his everyday routine. In a playful manner, he responds saying that it was through his understanding and love for Irish and its culture that he met his wife, an understanding helped by a year spent on an Irish scholarship at NUI Galway in 1998. “She had to love me”, he jests, “for I was the man with the information on Ireland”, their mutual passion drawing them together, ‘an Ghaeilge’ forming the foundation of their relationship.

Höglund was convinced that the Irish language wasn’t dead and thought it to be absurd that it took a ‘foreigner’ to see this. A man so driven to preserve something alien to his land, I was taken aback by his responses to my questions, in particular when I asked if he believed its doubters. He responds saying that ‘the language could die, that the human race could even vanish’ but as long as there is any trace of the language still in existence, he will be doing his ‘very best to save it’ and to ‘inspire others to do the very same thing’.

The love of the ‘Fionlannach’ for ‘An Ghaeilge’ being undoubtedly strong, I felt obliged to ask if he felt the Catholic Church’s had too strong an impression on the language.

‘I don’t believe so, in the slightest’, he says. ‘I’ve written and published erotica and the Church didn’t mind’.