Startling projection would see much of Dublin submerged by 2100

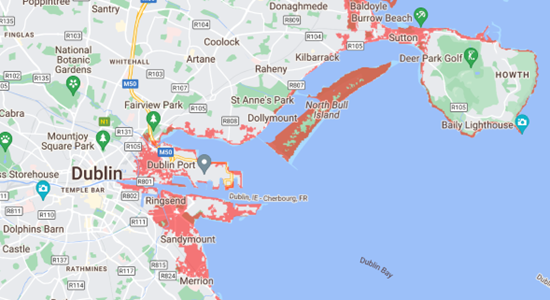

Much of Dublin’s coastline will be submerged in 1.7m of water due to rising sea levels by the year 2100, according to a presentation at the Dublin Climate Summit last year. But is this climate alarmism or a devastation we should plan for?

The summit warned in May that 8,500 buildings the length of the coast and along the River Liffey’s banks could be at risk of serious structural damage from floods. Critical infrastructure such as power plants and the financial services district could also be devastated, as indicated by climate technology company Cervest.

Sea levels along the Dublin coast are “rising more than they are falling” in the words of esteemed geographer and climatologist Professor John Sweeney, who spoke to The College View about the threat to the capital posed by climate change.

Professor Sweeney previously worked as a contributor to the Nobel Peace Prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “Dublin is on the hinge point for sea level rise because from North Dublin to Galway, land is still recovering from the glacial weight burden,” he said.

Certain inland parts of Dublin are also at risk due to its main rivers: River Liffey, River Tolka and River Dodder. Each one has old drainage systems which need restructuring and expose areas such as Drumcondra, Ballybough, Fairview and the Dodder Valley as far inland as West Dublin.

Source: River Tolka Flooding Study 2003

According to Professor Sweeney, sea level rise is inevitable going into the future. In the event of heavy rainfall caused by a low-pressure storm surge coupled with predictably higher tides, he expresses concern about the consequences for coastal areas.

He cited the Sutton tombolo, the low-lying Bull Island, Clontarf and Sandymount as examples of significant concern with land that “slopes down and away from sea after moving away from initial coastal strip.” When pressed about what can be done, Professor Sweeney conceded “we’ve passed the tipping point for big ice masses like Greenland and West Antarctica which could see 3-4m sea level rises in the centuries ahead.”

Preventative measures

Despite this rather gloomy forecast, potentially catastrophic flooding and permanent submergence are being addressed in the city. The Dublin City Development Plan 2016-2022 has demonstrated proactive mitigation in stalling major building developments in areas vulnerable to flooding like Sandymount, Irishtown, Ringsend and East Wall until construction of higher flood walls are completed.

Whilst accounting for the vulnerability of these areas, the development plan confidently validates the effectiveness of Clontarf’s existing rock armour, sea walls and promenades against potential rising tides. The plan also mentions how a recent construction of flood defences has the capacity to take a 20% increase in river flows. However, proposed extensive flood defences in the area are unlikely to be completed until 2027, according to Dublin City Council (DCC), but similar plans were rejected by residents in 2008.

In 2020, An Bord Pleanála published plans to construct demountable protective walls 1.2m high along the Clontarf embankment to protect 400 homes and businesses identified as increasingly in danger of flooding. The College View spoke to Green Party councillor Donna Cooney, who last year declared that the urge to update protective walls is being brought forward year on year – what were once-in-a-hundred years events were then expected to occur in 40 years and now they are happening “a few times a year”, she said.

A previous DCC plan to construct a 2.75m flood defence on the Clontarf coast road was shot down by residents in 2018. Despite Cllr Cooney’s concern about lack of prompt action, she said that she understands residents’ objections to the loss of “passive surveillance” in the interests of safety for women as a consequence of walking alone and out of sight behind the secondary flood defence wall due to its proposed height.

However, Cllr Cooney spoke of her preference for the building of a raised cycle lane doubling as a flood defence in place of simple sandbags which have been in situ for several years and remain the only flood defence along the portion of the promenade overlooking Dublin Port: “We could have adequate flood defence via a cycle way with walls on both sides and nature-based solutions like plant features to soak up excess rainwater,” she added.

“We could use this project as an example to show what’s possible internationally for cities like Lisbon and Barcelona” said Cllr Cooney in relation to flood protection infrastructure along Dublin’s most vulnerable coastal areas. To achieve a solution suitable to all, she believes the infrastructure must not impinge on the aesthetics, functionality or biodiversity of local amenities.

Impacts on other cities

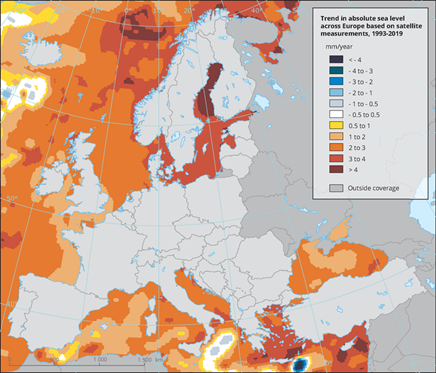

Dublin is not the only European city at risk of flooding by continuously rising sea levels. According to the Climate Change Post, thermal expansion of ocean water and loss of Antarctic ice sheets are on track to surpass IPCC estimates of sea level increase by at least one metre by 2100. This will threaten major coastal cities such as Lisbon, Marseille, Napoli, Athens and Istanbul.

between 1993-2019. Source: European Environment Agency

The difficulty in securing funding for flood defence measures from now onwards will relate to public appetite and passive attitudes to long-term measures which present no current concern to the average person in times of economic uncertainty and a cost-of-living crisis borne out of Covid. Without the will to act in the interests of generations decades down the line, the realisation that swathes of Dublin land may be flooded, costing millions of euros in damage, must be anticipated.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Research Report 2014-2020 on climate change coverage in Irish media suggests that such coverage needs to shift from a ‘science-based story to a social story’ in order to maximise the immediacy of danger. The research proposes that the media stop broadcasting the ‘settled science’ frame to a public who threaten to slip into the ‘uncertain science’ frame due to perplexity at scientific data they do not understand.

The report demonstrates how Irish media coverage will have to move beyond the dutiful reactive reporting on climate catastrophes and conferences to a more proactive all-year-round stance in order to truly enlighten the public as to what they should demand of their politicians in order to save Ireland’s coastal areas, particularly in Dublin.

Keith Kelly